Why Are Long Sentences A Bad Idea?

Research shows long sentences don’t work to keep communities safe.

Supporters of long sentences have traditionally argued that they improve public safety by deterring crime and keeping “dangerous” people off of the streets. However, both of these arguments have been disproven by research. In fact, long sentences go against the most recent research on how to deal with important problems like addiction and violence, and they cause immense harm along the way.

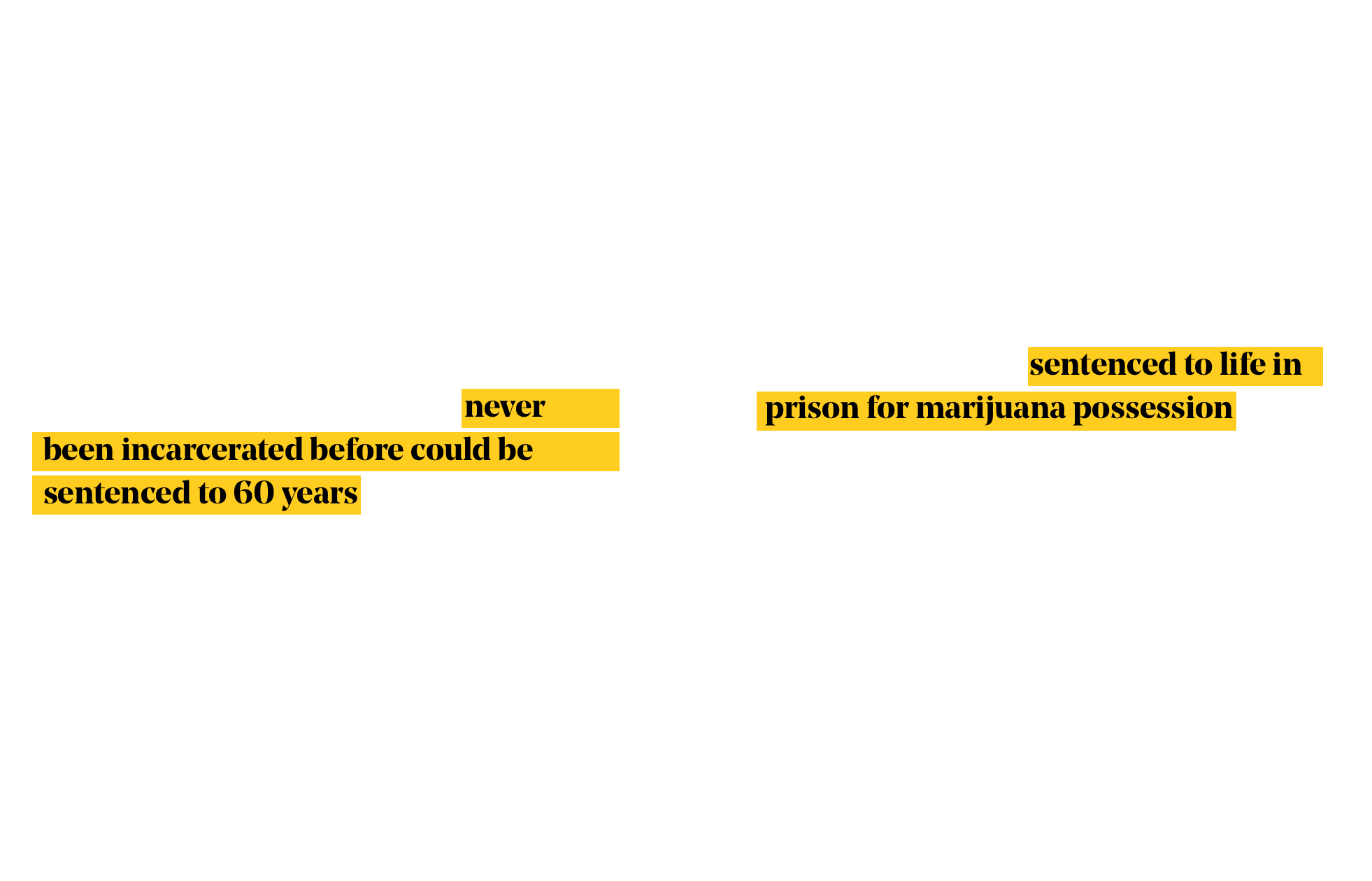

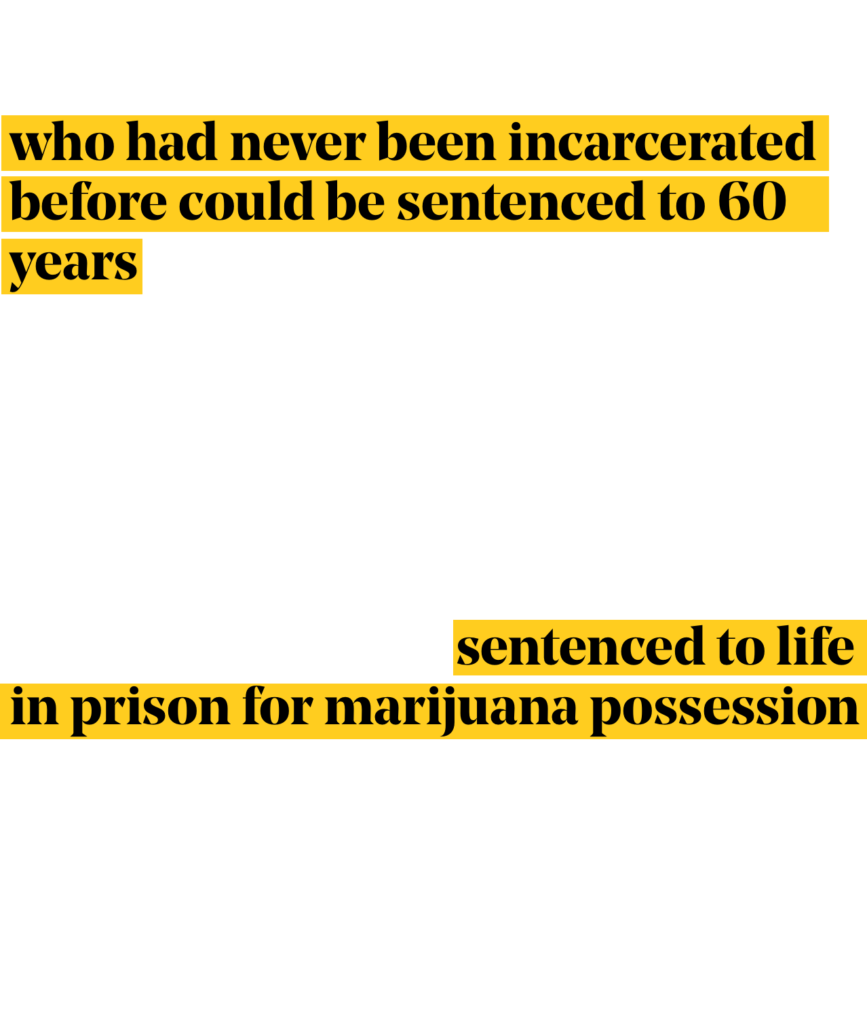

Deterrence, in the case of long sentences, is the idea that people will not commit crimes because they are scared of going to prison for a long time. But research shows that severe punishments do not increase public safety and don’t deter criminal behavior in the first place21. Very few people are familiar with the various penalties laid out in state statute22, let alone the arbitrary and complicated nature of habitual laws. On top of that, many behaviors that have been deemed illegal by statute are actions driven by addiction or poverty. For example, long prison sentences are highly unlikely to deter people from using drugs if they suffer from addiction.23

Locking people in prison to isolate them from society, often referred to as incapacitation, is also a misguided way to approach public safety. Research has shown that long prison sentences are ineffective as a crime control measure24 and evidence from multiple states proves that prison sentences for many offenses can be shortened with no effect on public safety.25 Very long and life sentences also make little practical sense in light of the extensive evidence that people are far less likely to break the law as they age.26

Long sentences are especially insidious when they are handed down for drug violations. Medical science has proven that addiction is a disease, and that relapse is a common aspect of recovery.27 Sending someone to prison does nothing to address the underlying addiction, and the lack of treatment and medication can increase the likelihood of relapse or overdose following release.28

Long sentences undermine public safety in other ways as well. People who serve long prison terms are routinely exposed to unsafe and unhealthy conditions, as recent investigations into prison conditions across Mississippi and the nation have demonstrated.29 While even short periods of incarceration can be devastating on a person’s stability after release, long sentences can make it even harder for people to successfully return home.30

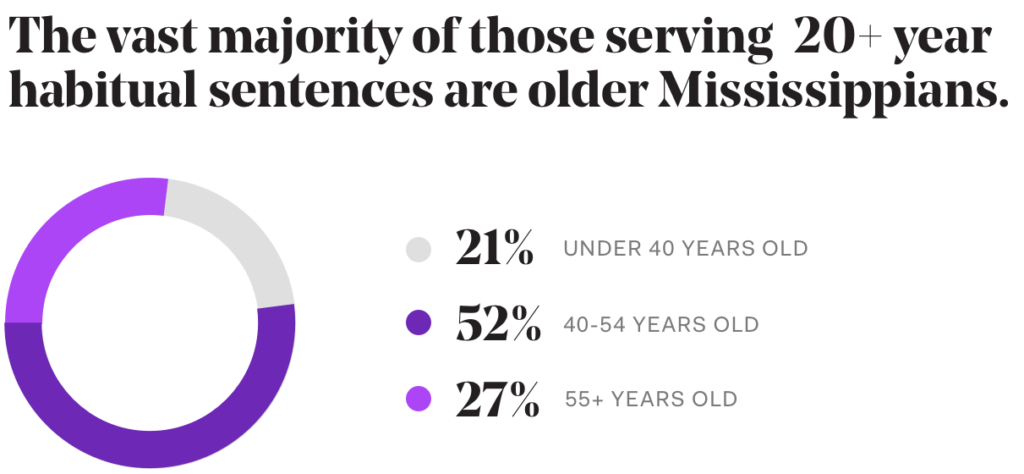

Long sentences subject people to age and die in prisons that are not equipped to handle their needs.

Long sentences force prisons to act as hospitals, and they have proven unfit for the job. As people age in prison, they are prone to the same health issues as aging people on the outside. On top of those issues, incarcerated people are more likely to develop chronic illnesses and infections, likely due to the stress associated with incarceration and substandard living conditions in jails and prisons.31 In fact, one study found that each year of incarceration results in a two year decrease in life expectancy.32 When people do grow ill in prison, they often receive poor medical care despite a constitutional guarantee to adequate medical care.33 Several private providers of in-prison medical care have been in the news recently for failing to properly diagnose and treat sick people, resulting in unnecessary surgeries, amputations, and deaths.34

Aging in prison also comes at great emotional and financial cost. Families are unable to care for their loved ones who grow ill in prison, further isolating people who are already suffering and denying people private time with their loved ones during their final days. And taxpayers foot an enormous bill for this cruel and ineffective system. In 2015, states spent $8.1 billion on prison health care.35

Long sentences disrupt family and community ties.

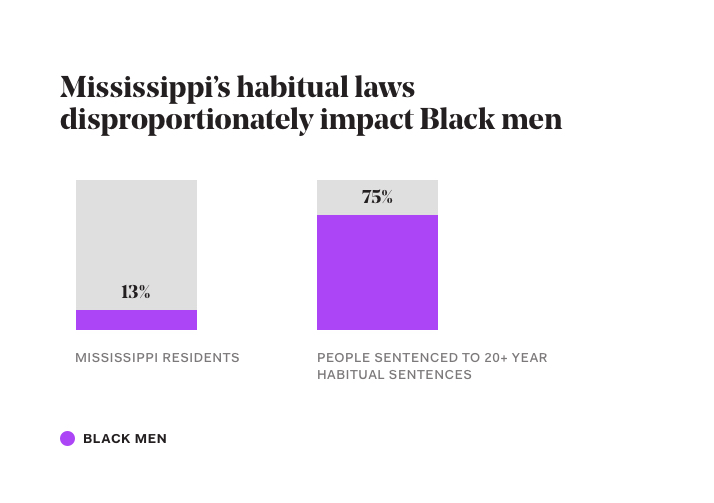

When people are separated from their family and community ties for decades, the impacts spill over into the rest of the family and future generations.36 When a family member is incarcerated, their loved ones face a host of challenges. When the incarcerated person is a parent, these consequences are especially severe. Over half of incarcerated parents reported that they were the primary financial support for their families.37 And when mothers are incarcerated, their children are often displaced from their homes and frequently placed in foster care.38 The trauma that these families experience leads to a wide range of negative impacts such as reduced earnings39, housing instability or homelessness40, poorer school outcomes4142, and mental health issues.4344 It also reinforces existing social inequalities.45

Given the extensive harms caused by incarceration, even the most serious crimes warrant careful consideration before an extreme sentence is imposed. Locking people up into old age or until they die without any opportunity for release undermines the value of redemption and stops the clock at the time of the crime, even after decades spent in prison. While violence and loss should be taken seriously, long sentences take a strictly punitive approach, rather than emphasizing healing and rehabilitation, which are both values supported by crime victims and survivors. In fact, more than six in 10 crime survivors prefer shorter prison sentences and would prioritize investments in education and job creation over harsh sentencing.46