Over a decade ago, researchers, policymakers, journalists, and individuals and family members harmed by prisons and jails helped define American mass incarceration as one of the fundamental policy challenges of our time. In the years since, policymakers and voters in red, blue, and purple jurisdictions have advanced criminal justice reforms that safely reduced prison and jail populations, expanding freedom and opportunities to tens of millions of Americans. After nearly forty years of uninterrupted prison population growth, our collective awareness of the costs of mass incarceration has fundamentally shifted–and our sustained efforts to turn the tide have yielded meaningful results.

Turning the Tide on Mass Incarceration

Expanding freedom and opportunity to millions

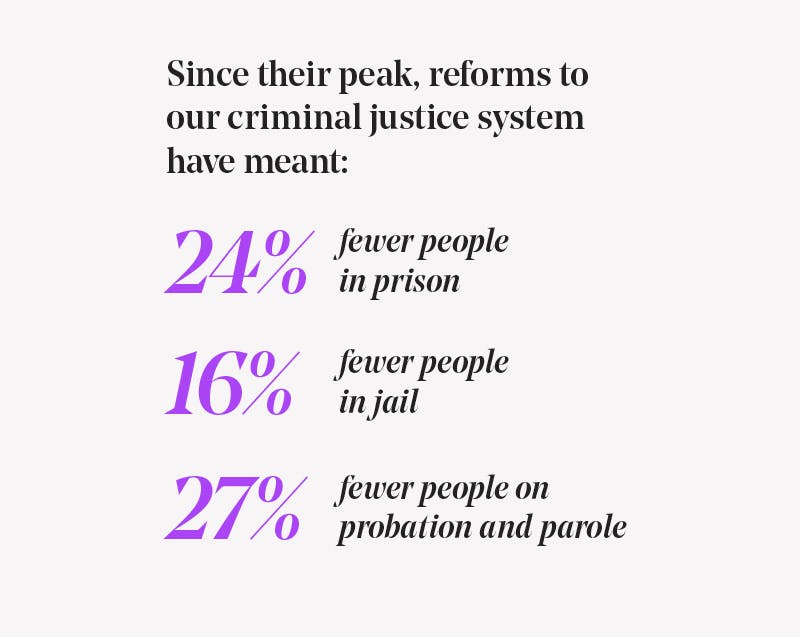

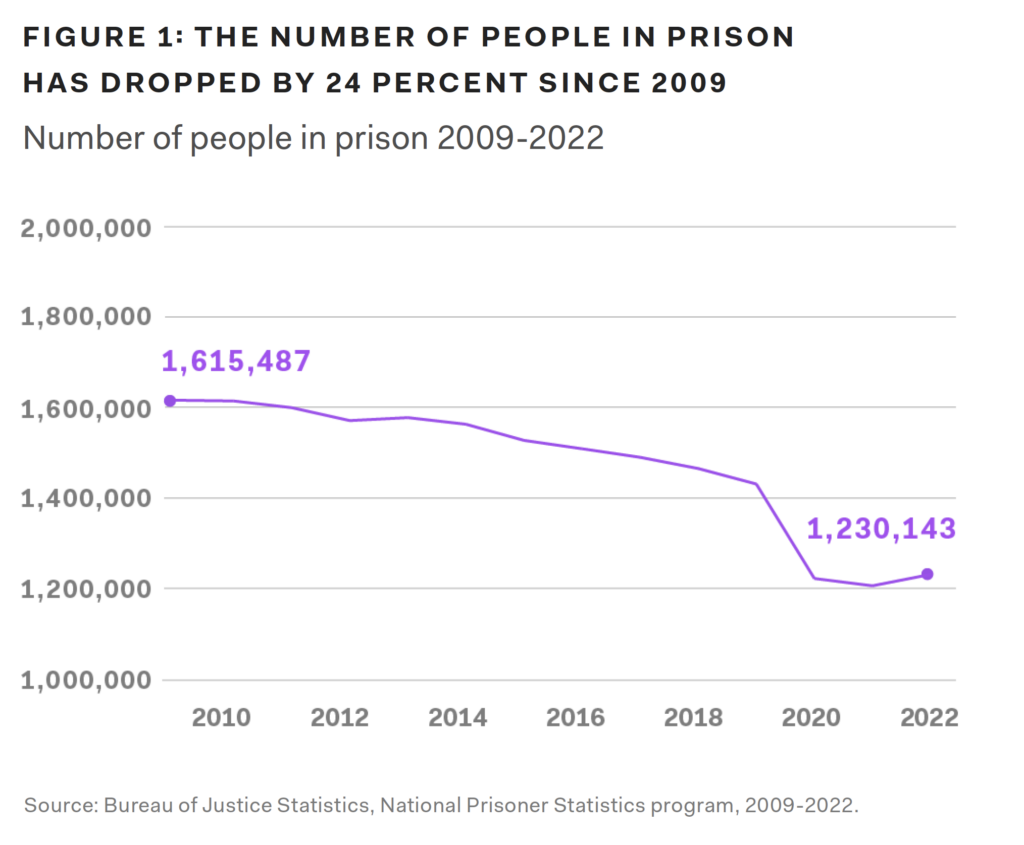

Since its peak in 2009, the number of people in prison has declined by 24 percent (see figure 1). The total number of people incarcerated has dropped 21 percent since the 2008 peak of almost 2.4 million people, representing over 500,000 fewer people behind bars in 2022. Absent reforms, more than 40 million more people would have been admitted to prison and jail over this period. The number of people on probation and parole supervision has also dropped 27 percent since its peak in 2007, allowing many more people to live their lives free from onerous conditions that impede thriving and, too often, channel them back into incarceration for simple rule violations.1

Make no mistake: mass incarceration and the racial and economic disparities it drives continue to shape America for the worse. The U.S. locks up more people per capita and imposes longer sentences than most other countries. Nearly 1-in-2 adults in the U.S. have an immediate family member that has been incarcerated, with lifelong, often multigenerational, consequences for family members’ health and financial stability. Yet the past decade of successful reforms demonstrate that we can and must continue to reduce incarceration. These expansions of freedom and justice–and the millions of people they have impacted–help define what is at stake as public safety has reemerged as a dominant theme in American public and political conversation.

“We have a robust body of research built over decades showing that jail stays and long prison sentences do not reduce crime rates.”

The longer-term encouraging trend was perforated by a one-year uptick in the number of people in prison since the peak in 2009 (up 0.4 percent from 2012-2013).3 The most recently released data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows another such increase; this time a 3 percent rise in the number of people in prison and jail from 2021 to 2022. What we know about the harms of mass incarceration–and about what actually advances safety–compels us to protect the progress we’ve made and ensure this increase is short-lived. We have a robust body of research built over decades showing that jail stays and long prison sentences do not reduce crime rates. And fortunately, we have an extensive and expanding body of research on what does work to reduce crime and keep communities safe. The evidence is clear: our focus must be on continuing and accelerating reductions in incarceration.

Black imprisonment rate drops by nearly half

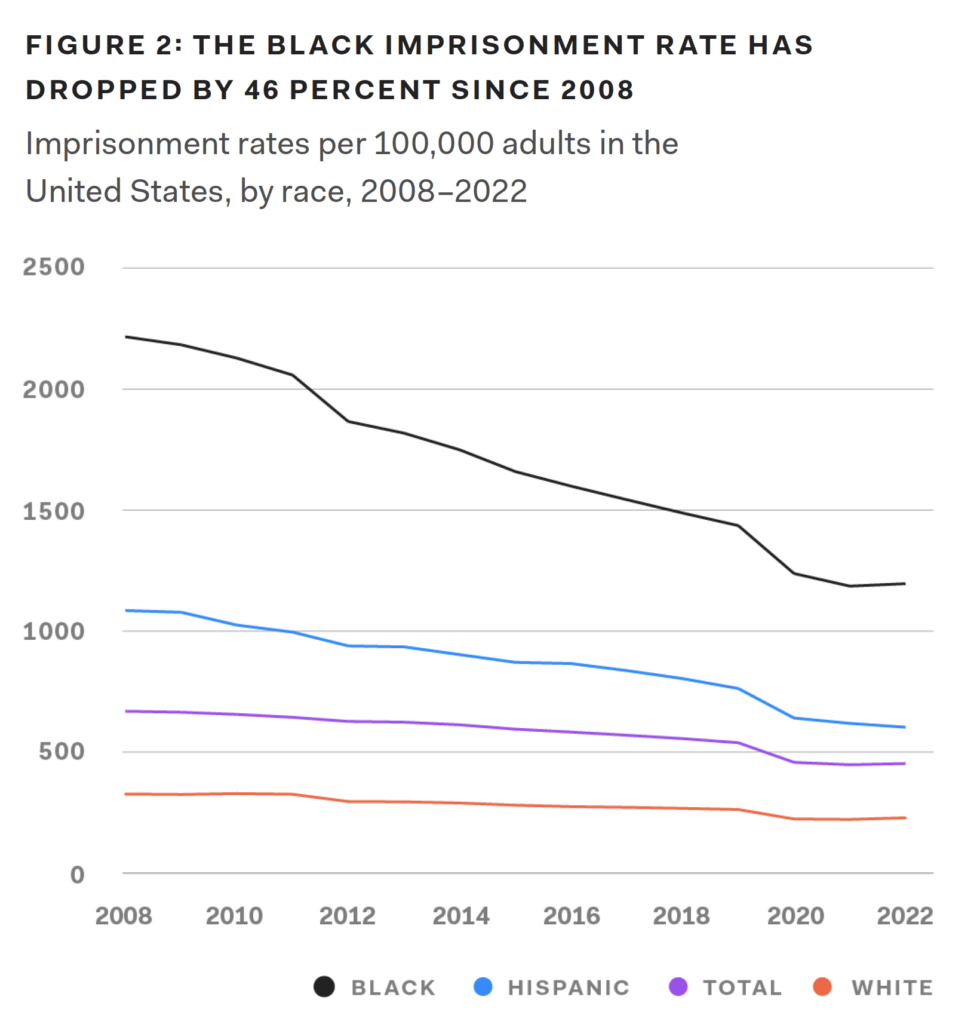

People directly impacted by incarceration and other leaders in the criminal justice reform movement have persistently called out how the unequal application of policies such as bail, sentencing, and parole (among others) drive massive racial disparities in incarceration. The concerted effort to reduce our prison population has had the most impact on the group that paid the greatest price during the rise of mass incarceration: Black people, and particularly Black men.

The Black imprisonment rate has declined by nearly 50 percent since the country’s peak imprisonment rate in 2008 (see figure 2). And between 1999 and 2019, the Black male incarceration rate dropped by 44 percent, and notable declines in Black male incarceration rates were seen in all 50 states. For Black men, the lifetime risk of incarceration declined by nearly half from 1999 to 2019—from 1 in 3 Black men imprisoned in their lifetime to 1 in 5. While still unacceptably high, this reduction in incarceration rates means that Black men are now more likely to graduate college than go to prison, a flip from a decade ago. This change will help disrupt the cycle of incarceration and poverty for generations to come.

“From 2012-2022, 45 states saw reductions in crime rates, while imprisoning fewer people...”

Expanding safety and justice together

The past decade-plus of incarceration declines were accompanied by an increase in public safety. From 2012-2022, 45 states saw reductions in crime rates, while imprisoning fewer people, with crime falling faster in states that reduced imprisonment than in states that increased it. This is in keeping with the extensive body of research showing that incarceration is among the least effective and most expensive means to advance safety. Our extremely long sentences don’t deter or prevent crime. In fact, incarcerating people can increase the likelihood people will return to jail or prison in the future. Public safety and a more fair and just criminal system are not in conflict.

“We have also seen dramatic progress on the public opinion front, with a clear understanding from voters that the criminal justice system needs more reform, not less.”

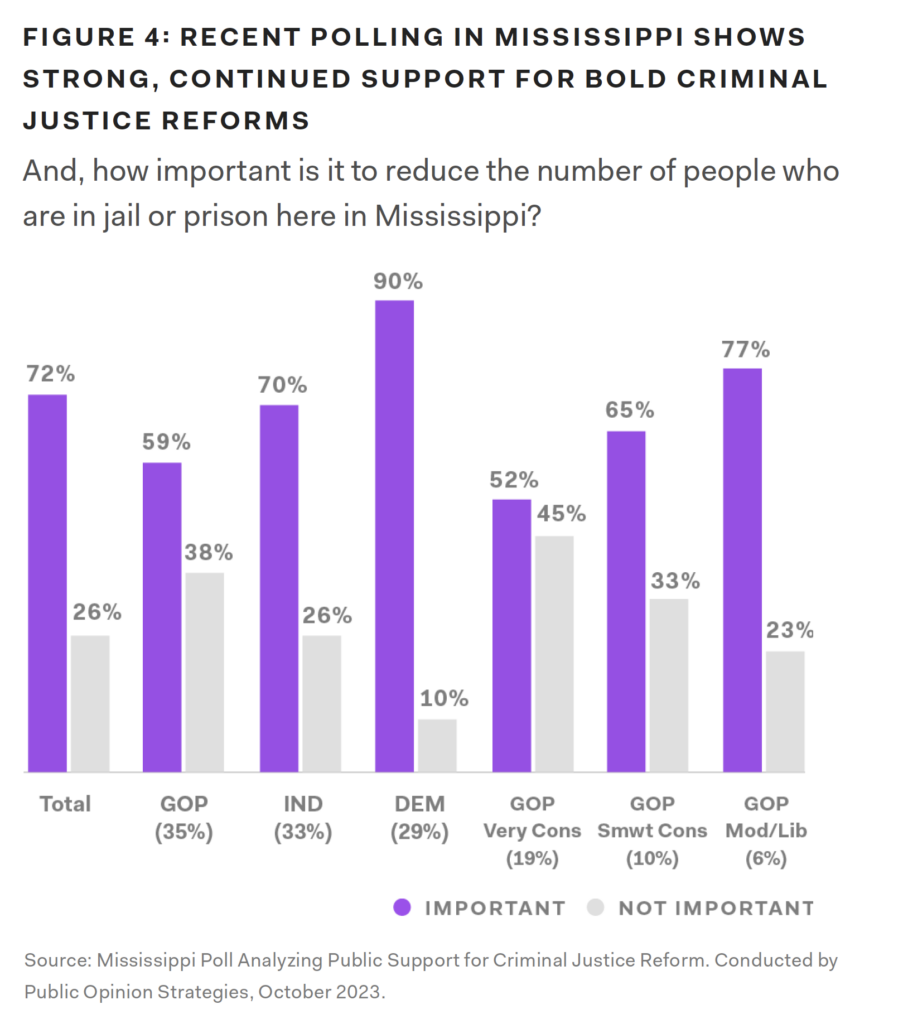

“...72 percent of Mississippians, including majorities from both parties, believe it is important to reduce the number of people in prison.”

Strong and widespread support for reform

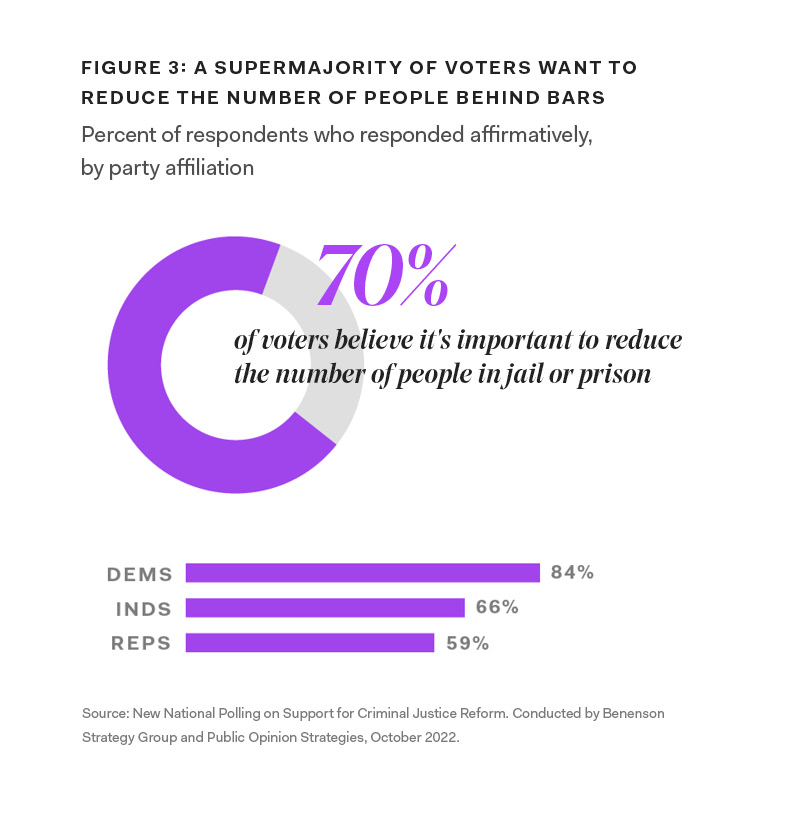

We have also seen dramatic progress on the public opinion front, with a clear understanding from voters that the criminal justice system needs more reform, not less. Recent polling shows that by a nearly 2 to 1 margin respondents prefer addressing social and economic problems over strengthening law enforcement to reduce crime. Nearly nine-in-ten Black adults say policing, the judicial process, and the prison system need major changes for Black people to be treated fairly. Seventy percent of all voters (see figure 3) and 80 percent of Black voters believe it’s important to reduce the number of people in jail and prison. Eighty percent of all voters, including nearly three-fourths of Republican voters, support criminal justice reforms.

This is not only a blue state phenomenon. Recent polling in Mississippi indicates strong support across the political spectrum for bold policies that reduce incarceration. For example, according to polling from last month, 72 percent of Mississippians, including majorities from both parties, believe it is important to reduce the number of people in prison (see figure 4). Perhaps most tellingly, across the country victims of crime also support further reforms to our criminal justice system over solutions that rely on jail stays and harsh prison sentences.

Continuing the momentum

Despite this progress and the clear evidence of public support for more reform, mass incarceration is still a reality, and it continues to exact enormous human and economic costs, particularly for Black communities. At the 2021 rate of prison decline, it would take more than seven decades to undo the damage of mass incarceration. And, for the first time in almost a decade, the prison population began to go up in 2022.

We are at an inflection point: we can continue to rely on the failed mass incarceration tactics of the past, or chart a new path that takes safety seriously by continuing to reform our broken criminal justice system and strengthening families and communities.

Endnotes

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics program 2008-2022, Annual Survey of Jails 2008-2022, Census of Jails 2008-2022, Annual Probation Survey 2007-2021, Annual Parole Survey 2007-2021.

- The peak population years were 2009 (prison), 2008 (jail), and 2007 (supervision).

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics program, 2009-2022.

- Imprisonment rate changes from: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics program 2012-2022. Crime rate changes for Illinois, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas from: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer, 2012-2022. A change in the method of reporting crime statistics to the FBI resulted in less reliable data for certain states, therefore crime data was pulled from state government sources for states with lower reporting. Additional crime rate change data from California Department of Justice, "Crime in CA 2022," and New York Division of Criminal Justice Services, Index Crime Data Table, 2012-2022.

Tell the world; share this article via...

Read related articles:

Get Involved

We need your help to move America forward. Learn what you can do.