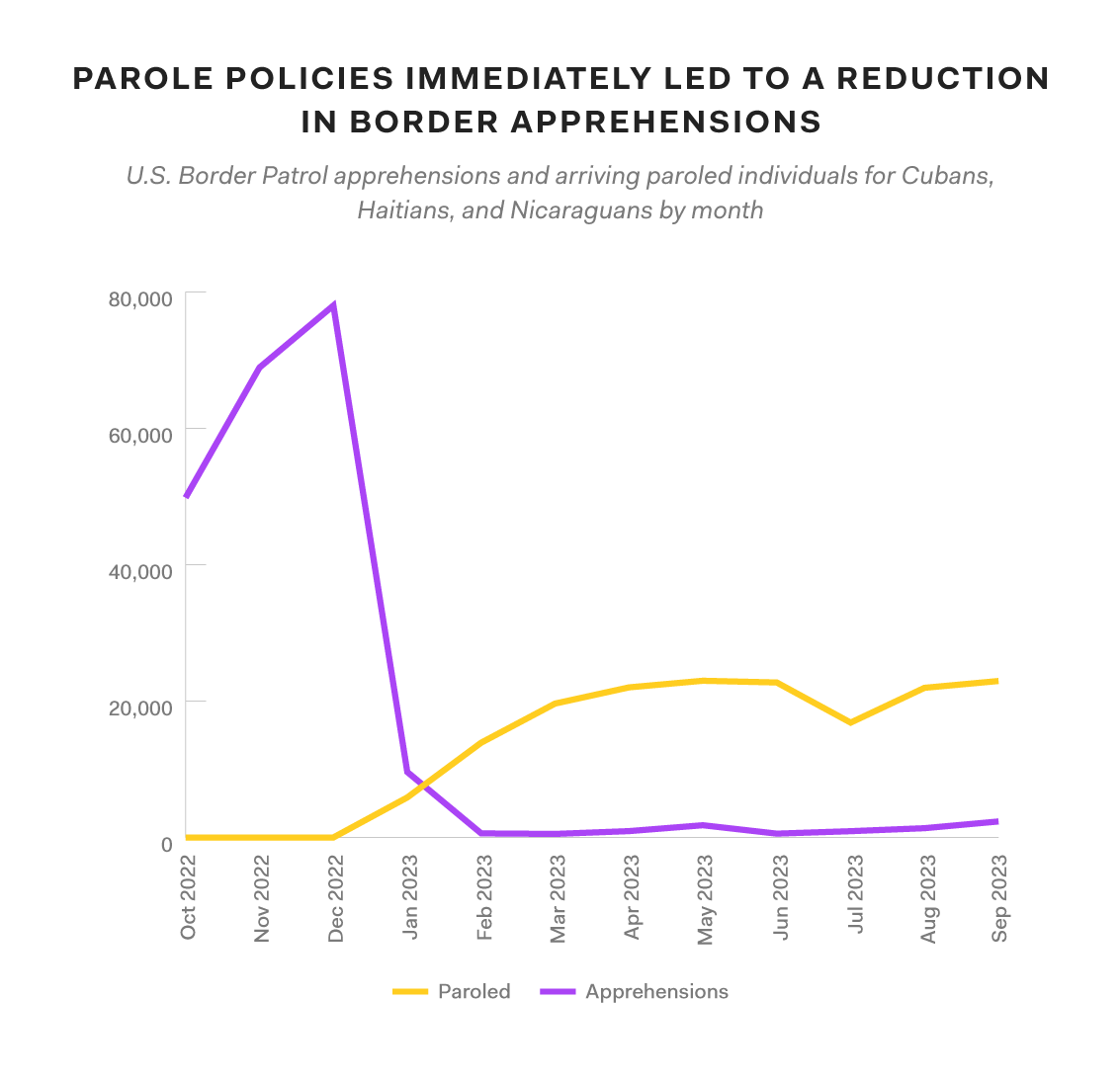

FWD.us has been advocating for new legal pathways, including humanitarian parole, refugee resettlement, the addition of temporary work visas, and improving family-based migration, as the most effective policies to address the unprecedented levels of forced migration in the Western Hemisphere.

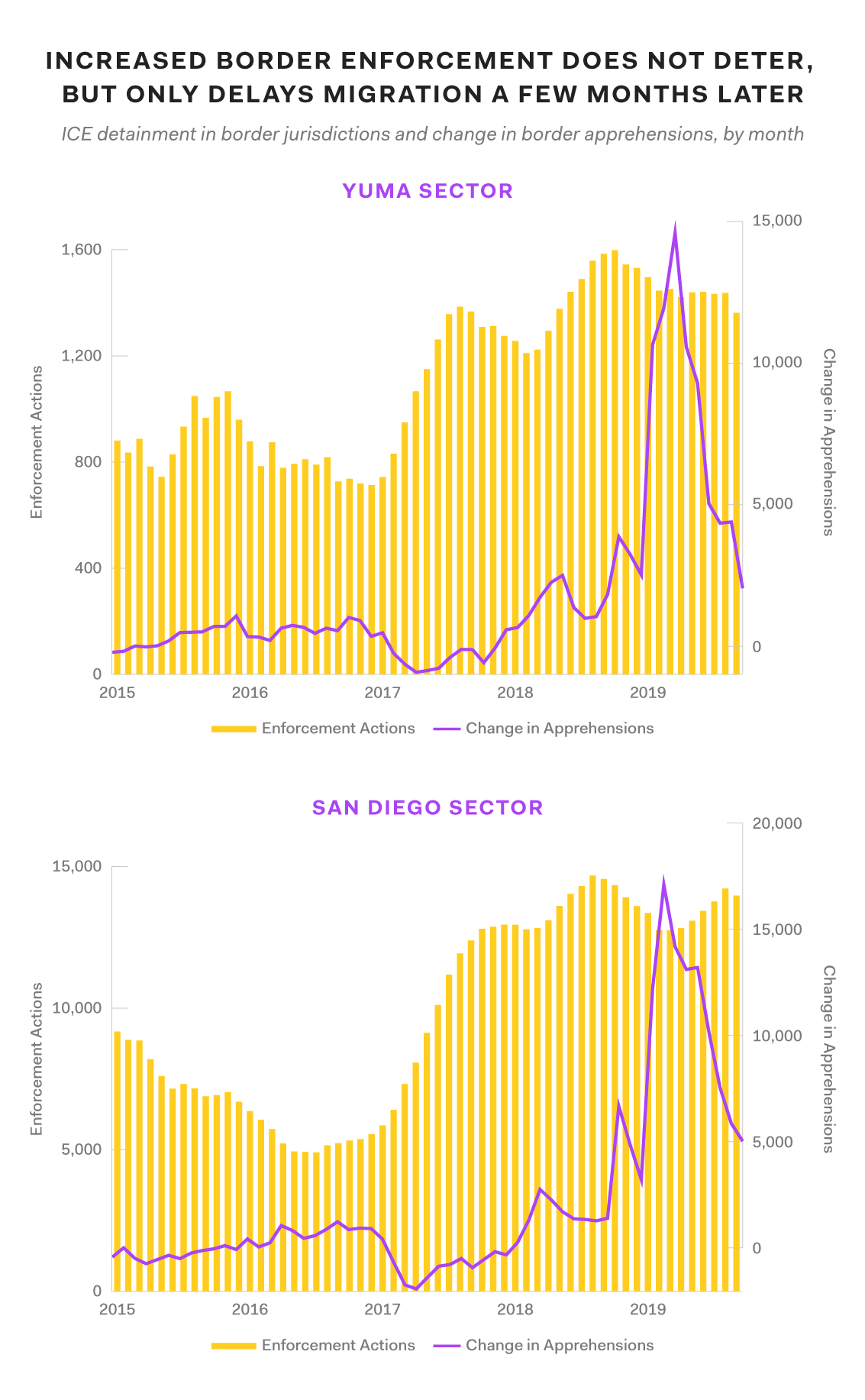

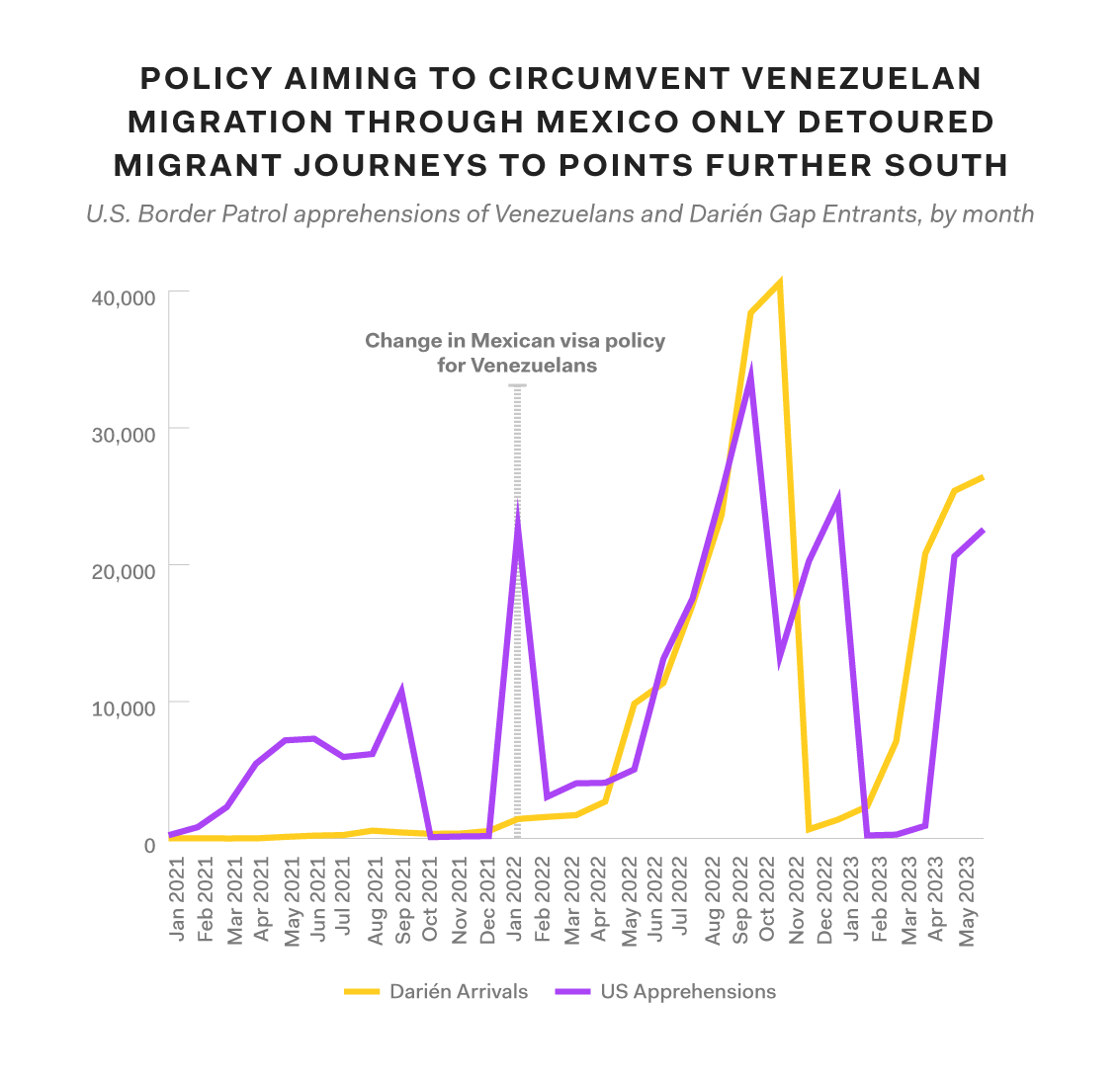

David Leblang, FWD.us Immigration Fellow and Ambassador Taylor Professor of Politics and Compton Professor of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, has spent more than two decades researching the journeys of international migrants around the world. His quantitative research reveals that more aggressive border enforcement tactics and offshoring immigration control to other countries do not ultimately deter migrants, but only delay their arrival or detour their journeys. Instead, Professor Leblang’s research suggests that the more effective response to widespread migration in the region is to create more legal pathways, both for those escaping violence and for those who would like to contribute economically to the United States.