High-skilled immigration is good for America — it creates jobs, raises wages, and keeps America globally competitive — particularly as the U.S. economy struggles to recover from the coronavirus crisis. But the existing high-skilled immigration system is outdated, and thousands of highly skilled workers, many of them educated in the United States, are left with few options other than to take their skills elsewhere. To retain this invaluable competitive advantage, Congress must expand high-skilled immigration options to keep them here.

High-Skilled Immigration

5 Things to Know

9 million Americans employed at immigrant-owned firms

262 jobs created for every 100 international grads working in STEM fields

50% of billion-dollar valued startups have an immigrant founder

1| High-skilled immigration creates jobs and raises wages for Americans

Highly skilled immigrants are an essential part of the United States’ workforce, filling critical labor gaps and contributing specialized skills, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields where demand for knowledgeable workers is consistently high.

When U.S. businesses can hire the skilled talent they need, they can produce more, innovate, and expand, creating a “multiplier effect” that extends benefits to American workers and the broader economy.

This leads to higher wages, increased productivity, and lower unemployment for U.S.-born workers, as well as more jobs — in fact, every 100 international graduates working in STEM fields is associated with the creation of an additional 262 jobs.

Immigrants are also job-creators, starting businesses at nearly twice the rate of native-born Americans and employing nearly 9 million Americans. This is especially true for immigrants in STEM fields; more than 50% of startups valued at $1 billion or more have at least one immigrant founder, creating an average of 760 jobs each. Household names like Google, Uber, Zoom, Postmates, and Tesla all have immigrant founders.1

All of these factors allow the United States to remain the economic and technological leader on the global stage.

2| High-skilled immigration is America’s competitive advantage

America’s attractiveness as a destination for skilled workers across the globe is an invaluable competitive advantage, providing a robust pipeline of specialized talent in critical fields.

In the 21st century, technological innovation is key to economic growth. Skilled immigrants lead a large share of scientific and technological research and development, especially in fields like artificial intelligence, which are critical to maintaining our global competitiveness and national security. High-skilled immigrants are also highly innovative, filing patents at high rates and boosting innovation among their peers.

All of these factors allow the United States to remain the economic and technological leader on the global stage. By attracting this talent away from competing countries — like China — the U.S. can preserve this advantage.

The United States has invested significantly in these graduates... Allowing and encouraging them to stay should be a top priority, instead of sending them away to contribute those skills elsewhere.

3| International graduates of American universities make up an increasing share of the U.S. high-skilled workforce

America’s highly skilled foreign-born workforce is increasingly made up of individuals who have earned an American education. In 2018, more than half of all advanced STEM degrees awarded by U.S. colleges and universities went to international graduates.

Many international graduates also have valuable work experience in the United States thanks to Optional Practical Training (OPT), a program that allows international graduates to work for a U.S. employer in their field of study for up to three years. In FY19, more than 200,000 graduates were working on OPT.

After completing their studies, most graduates wish to stay and seek long-term employment in the U.S. Last year, more than half of all H-1B applicants had an advanced degree from a U.S. college or university.

The United States has invested significantly in these graduates, and they are well-prepared to contribute those skills to the economy here. Allowing and encouraging them to stay should be a top priority, instead of sending them away to contribute those skills elsewhere.

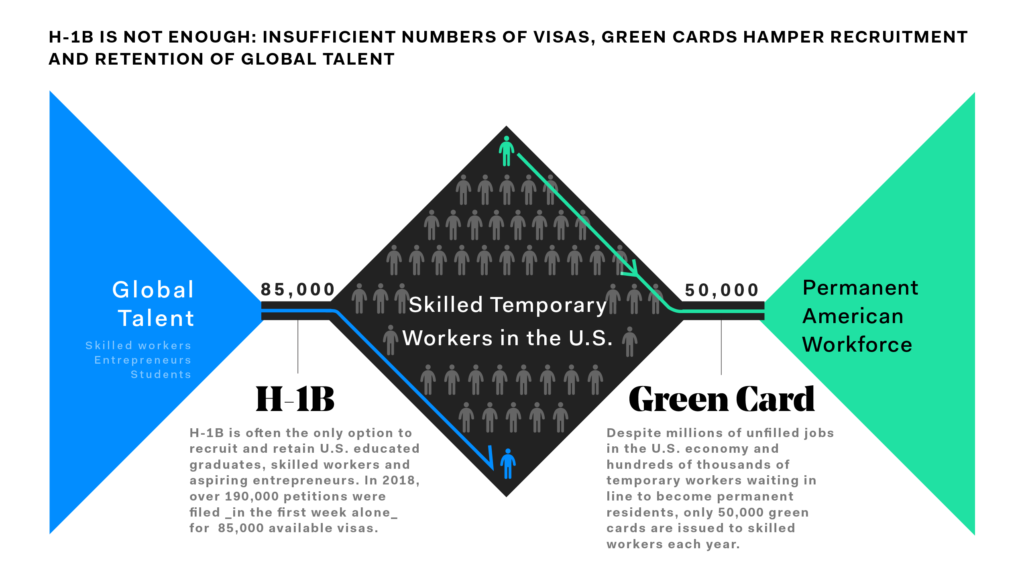

4| H-1B is the only option available for most skilled workers, but it’s not enough

The H-1B visa allows U.S. employers to hire foreign-born workers temporarily in “specialty occupations” that require a high level of education or technical knowledge. There are nearly 600,000 individuals working in the U.S. with an H-1B visa today in every sector of the economy.

Over time, the H-1B program has expanded to become the primary immigration option for all highly skilled workers, largely because the U.S does not have dedicated immigration options for entrepreneurs, graduates of U.S. schools, medical professionals, and researchers, among other occupations.

Unfortunately, the limited availability of H-1B visas is not enough to meet the needs of U.S. employers, leaving critical roles unfilled and forcing highly-skilled, U.S.-educated professionals to leave the U.S. if they cannot secure a visa.2 In recent years, demand for H-1B visas has consistently exhausted the number available as set by Congress within just one week.

And when skilled immigrants apply for permanent residency, an ever-worsening backlog keeps them waiting years to receive their green card after they’ve qualified.3 These backlogs trap skilled workers in limbo, keeping them temporary status, limiting the contributions they can make, preventing them from planning for their own futures, and exposing them to further immigration challenges. 4

For more on barriers to recruiting and retaining global talent in the U.S., read our report here.

Restricting high-skilled immigration forces U.S. employers to move jobs and production offshore, without a measurable boost in employment for American workers.

5| Restricting skilled immigration sends jobs abroad and undermines global competitiveness

Immigration is a clear driver of economic growth, and restricting or eliminating immigration opportunities will have serious negative consequences as the U.S. tries to rebuild our economy and recover from economic devastation brought about by the coronavirus crisis. Overall cuts to legal immigration levels like those proposed by the White House would shrink the economy by 2% and cost 4.6 million jobs over 20 years.

Restricting high-skilled immigration forces U.S. employers to move jobs and production offshore, without a measurable boost in employment for American workers. When President Trump announced a ban on new high-skilled visas in June 2020, business executives predicted the move would send more jobs to Canada – and in fact, this is exactly what has happened.

These restrictions make the U.S. less attractive to global talent, jeopardizing our skilled workforce. International student enrollments have been declining in recent years, and backlogged visa holders are increasingly looking to abandon the wait and move to countries with more flexible policies, like Canada.

To protect America’s competitive advantage, Congress should expand high-skilled immigration

Congress can take action now to allow more highly-skilled individuals to work and stay in the U.S., including:

- increase the number of work visas and green cards issued each year by establishing dedicated programs for key groups like international graduates, entrepreneurs, and medical professionals.

- exempt spouses and children from quotas and allow spouses to apply for work authorization, so that the full number of workers can be admitted each year and families can stay together.

- eliminate discriminatory per-country caps and clear the green card backlog.

For more on this topic, follow Andrew Moriarty on Twitter (@a_moriarty) and read our report on modernizing the high-skilled immigration system.

Get in touch with us:

Andrew Moriarty

Deputy Director of Federal Policy

Footnotes

- Highly-skilled immigrants also drive America’s leadership in health and wellness, making up an estimated 17% of healthcare workers in the U.S., including 28% of physicians and surgeons. 40% of medical scientists in pharmaceutical research and development, and 40% of researchers at top cancer research centers, are foreign-born.

- In FY19, the number of advanced U.S. degree holders seeking H-1Bs exceeded the total worldwide cap (90,000 vs. 85,000), guaranteeing many U.S. graduates would be turned away.

- Country-specific quotas create exceptionally long wait times for immigrants from India and China, who make up the majority of H-1B visa recipients; the predicted wait time for Indian immigrants today is more than 50 years.

- The H-1B visa significantly limits workers’ abilities to change employers, accept promotions, or adjust the location of their work; this has been a serious challenge for foreign-born doctors struggling to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers on temporary visas are also vulnerable to sudden changes in policy, as illustrated by the thousands of immigrant families separated and stranded abroad by President Trump’s nonimmigrant visa ban earlier this year.