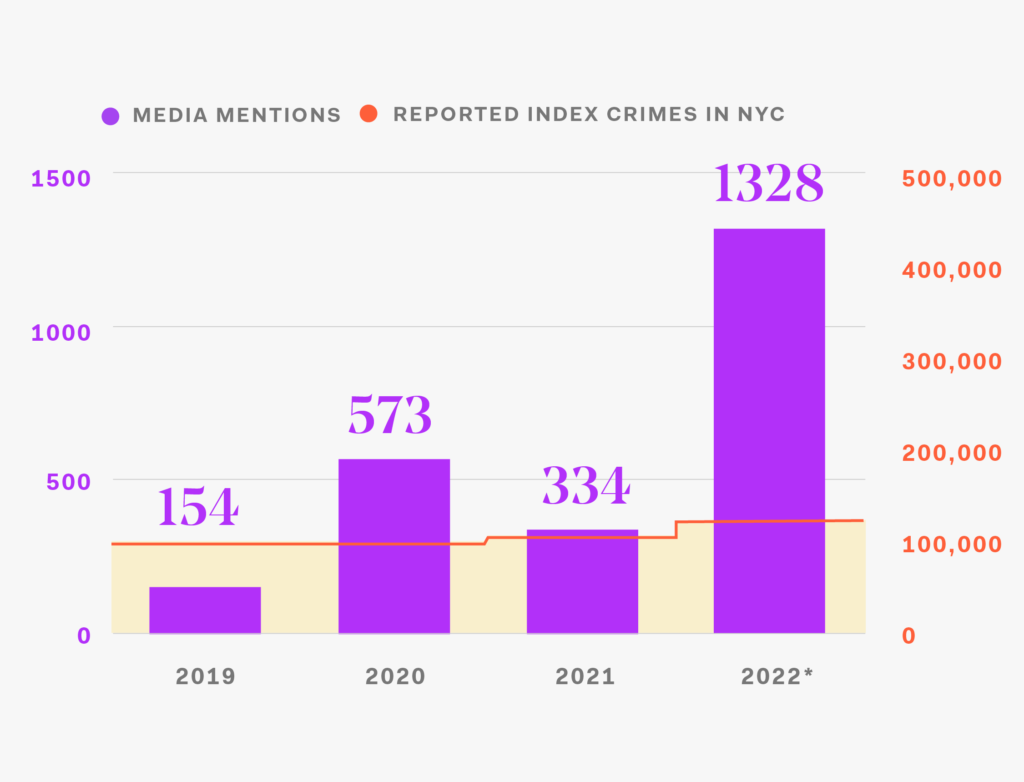

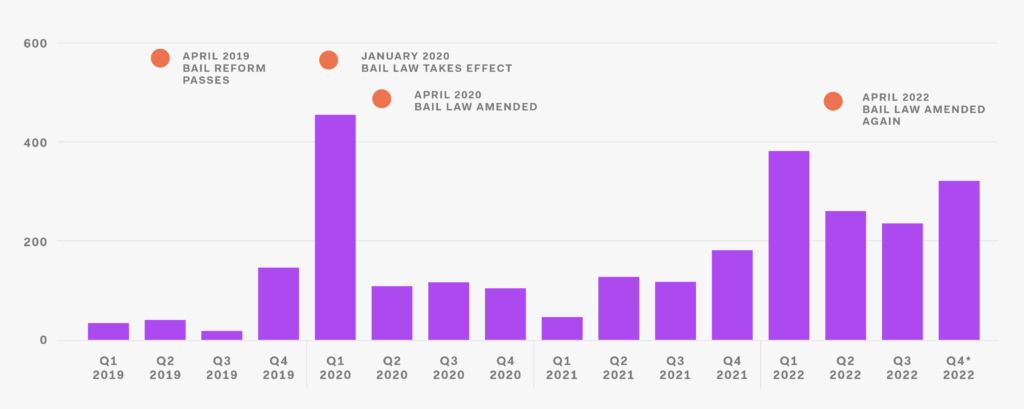

Media Mentions

In order to analyze the ubiquity of media coverage of bail reform and crime, the number of articles mentioning both “bail reform” and “crime” was compiled using Lexis Nexis News search tools. The search terms “bail reform” and “crime” were combined to find any article published in New York state that included both terms. This search was run month by month, to identify the number of articles within each monthly time period from January 2019 through November 2022 (unless otherwise noted). This search was compiled on November 15, 2022, meaning that results for November 2022 are incomplete. To compare year to year, data on crime and number of published articles was adjusted to project the total for 2022 if trends were to continue.

Bail Eligibility

In order to determine bail eligibility and therefore which cases fell in the mandatory release category and be most impacted by bail reform, several estimations had to be made with regards to broad categories allowing bail to be set. The goal of this analysis was to isolate bail ineligible cases to better understand the impact of bail reform on people who were very likely to be impacted by it, therefore estimations generally erred on the side of including cases as bail eligible when there was ambiguity in the data or when the possibility of discretion could put those cases into a bail eligible category.

When ambiguity existed in the data, broad categories were used to try to classify cases as either “bail eligible” or “bail ineligible.” These categories include: charges that require certain conditions (unidentifiable in pretrial dataset) be true in order to be bail eligible; any crime causing the death of another person; persistent felony offender status; and “harm on harm.”

The misdemeanors criminal contempt and criminal obstruction of breathing or blood circulation, as well as the felonies criminal contempt and unlawful imprisonment require that the underlying charge be a domestic violence offense in order to be bail eligible. DCJS pretrial data contains no indicator for domestic violence. Cases that were possibly bail eligible based on these conditions were estimated to be bail eligible. This estimation is based on the fact that these charges are most often levied in domestic violence cases according to the experience of former practicing New York defense attorneys. Cases that were included as bail eligible based only on the estimation of an underlying domestic violence charge constituted 7.9 percent of the pretrial dataset.

Felony failure to register as a sex offender if the person charged is required to register as a level 3 sex offender. DCJS pretrial data contains no indicator of sex offender status. These cases were estimated to be bail eligible due to the relatively small subsample size and the likelihood that some of these cases would involve individuals required to register as level 3 sex offenders. Cases that were included as bail eligible based only on estimation of level 3 sex offender status were a very small subset of the pretrial dataset (less than 0.05%).

Felony burglary in the second degree requires that the offense occur in the living area of a dwelling in order to be bail eligible. DCJS pretrial data contains no indicator as to whether burglary occurred in the living area of a dwelling. These cases were estimated to be bail eligible based on the advice of former New York defense attorneys and the intention of this analysis to more accurately isolate bail ineligible cases. Cases with the top charge of felony burglary in the second degree that were included as bail eligible constituted 1.3% of the pretrial dataset.

Any crime causing the death of another person is bail eligible. DCJS pretrial data does not contain any indicator for death of a victim (besides charges like homicide that necessarily result in the death of a person). New York Penal Law was examined for offenses that include causing the death of a person. In this dataset, the number of cases that could have caused death and were not otherwise bail eligible constituted a very small subset (less than 0.05%). These cases all included offenses that result in the death of a person and were therefore all estimated to be bail eligible.

Any felony offense where the defendant would qualify as a persistent felony offender as defined by New York Penal Law is bail eligible. DCJS pretrial data does not include any indicator for persistent felony offender status, but it does include prior felony conviction counts. There is no indicator of the date of prior felony convictions, making estimations of persistent felony offender status difficult. After analyzing possible combinations of prior felony convictions and conferring with former New York defense attorneys, only those cases that seemed most likely to possibly be qualified as persistent felony offender status were included as bail eligible. Cases that were included as bail eligible based on persistent felony offender status constituted a small subset of the dataset (1.1%).

Cases that include offenses that would qualify as “harm on harm” are bail eligible. In order for a case to be considered “harm on harm,” a person charged must either be released on a felony and arrested for a felony OR released on a felony and arrested for a class A misdemeanor causing harm to an identifiable person or property or criminal possession of a firearm OR released on a class A misdemeanor causing harm to an identifiable person or property or criminal possession of a firearm and arrested for a felony. DCJS contains indicators for pending felony arrests and pending misdemeanor arrests, however, pending misdemeanor arrests are not categorized by severity. Cases with a pending felony arrest and current charges that were class A misdemeanors involving harm to an identifiable person or property were included as bail eligible. “Harm to an identifiable person or property” is a broad condition based on the discretion of the court, and does not have a universal definition in the New York Penal Law. In order to estimate bail eligibility, a broad definition of this condition was used, including any offenses that could possibly be interpreted as harm to person or property. Cases that were included as bail eligible based on the estimated harm on harm condition constituted 5.2% of the dataset.

Altogether, 19.3% of the dataset fell clearly into bail eligibility, 66.4% fell clearly into bail ineligibility (the group referenced as 'impacted by bail reform' in this report), and 14.3% were in one of the listed categories and were classified as bail eligible for the purposes of this analysis.

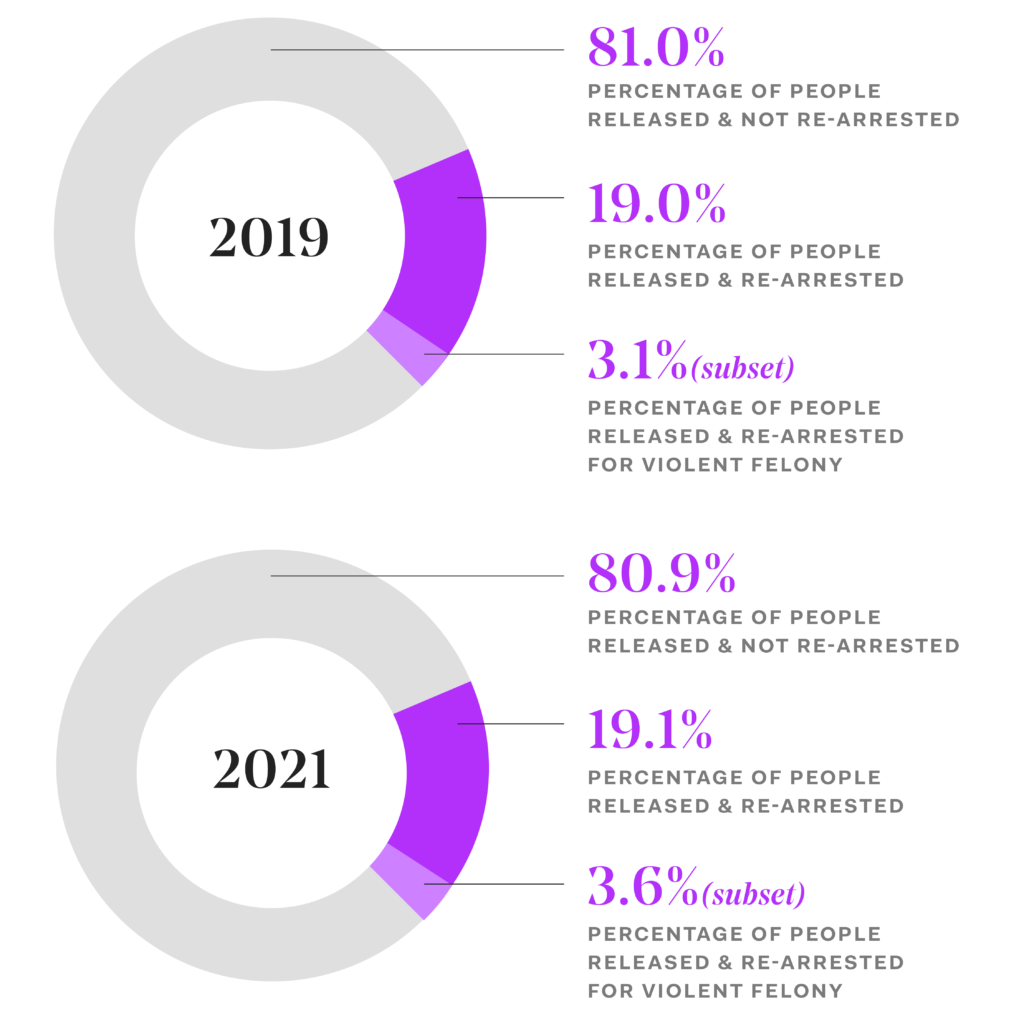

Re-Arrests and Failure to Appear

For this analysis, FWD.us analyzed re-arrest rates and failure to appear rates among bail eligible and bail ineligible cases. In order to make an apples to apples type comparison, bail eligibility was defined as it existed after bail reform amendments were implemented in July 2020. Using these conditions, re-arrest rates and failure to appear rates were compared among cases that would have been bail eligible/ineligible pre and post bail reform. Because the latest DCJS pretrial data was produced in May of 2022, arraignments in the fourth quarter of 2021 would not have reached a minimum of six months pending as of the creation of this data. For this reason the arraignments in the fourth quarter of 2021 were excluded from re-arrest and failure to appear rate analyses.

Re-arrest rates were compiled by analyzing the number of cases with re-arrests that occurred sometime between arraignment and final disposition. Failure to appear rates were estimated by analyzing the number of cases in which a bench warrant was issued sometime between arraignment and final disposition. Re-arrest and bench warrant rates were measured as a percentage of releases, or arraignments that resulted in release on own recognizance, non-monetary release conditions, or in which bail was paid within 5 days.