“Creating a straightforward path for international student graduates to work and live permanently in the U.S. is a smart policy for international students. It’s an even smarter policy for America.”

The United States could increase its competitiveness in the global race for talent with a straightforward process for the 100,000 international students projected to graduate from U.S. colleges and universities each year who want to stay and work permanently in the country. According to FWD.us estimates, allowing such graduates to work permanently in the U.S. could add up to $233 billion in wages to the U.S. economy this decade, including $65 billion in combined federal, state, and local taxes. Such a policy could also reduce our STEM-related talent shortages by a quarter this decade. Congress should immediately introduce legislation allowing international students a direct avenue to permanent residency after their graduation.

The U.S. has an opportunity to bolster its leadership in the global talent race

For decades, the U.S. has been the global leader in higher education and the top destination for international students from around the world. The U.S. offers both superior educational opportunities and an attractive, supportive environment for international students. Consequently, the U.S. saw the number of new international students grow throughout much of the previous decade, bolstering this incredible competitive advantage in recruiting global talent.

But this competitive edge has started to dull as other countries ramp up their efforts to recruit prospective students. For the first time in many years, the total number of international students in the U.S. decreased in 2019, and continued decreasing even further after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. hosts more international students than any other country in the world. But 50% more international students study in Australia, Canada, and the U.K. combined than in the U.S., much higher than in 2015 when about the same number studied in the U.S. as in these three countries.

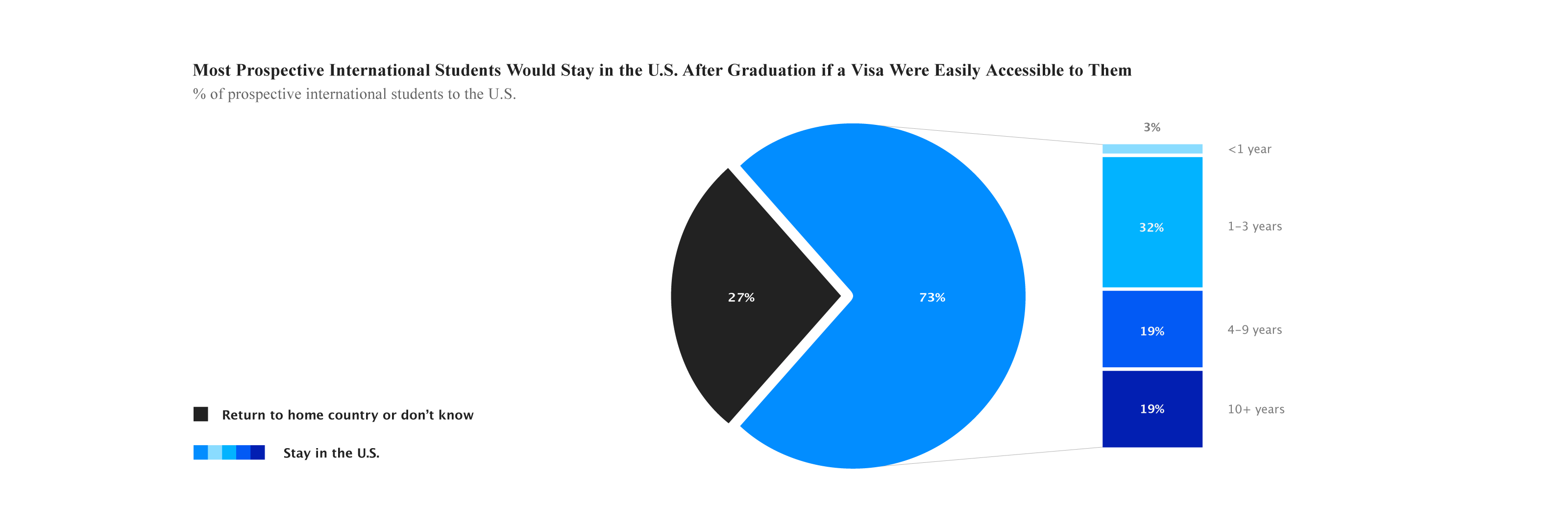

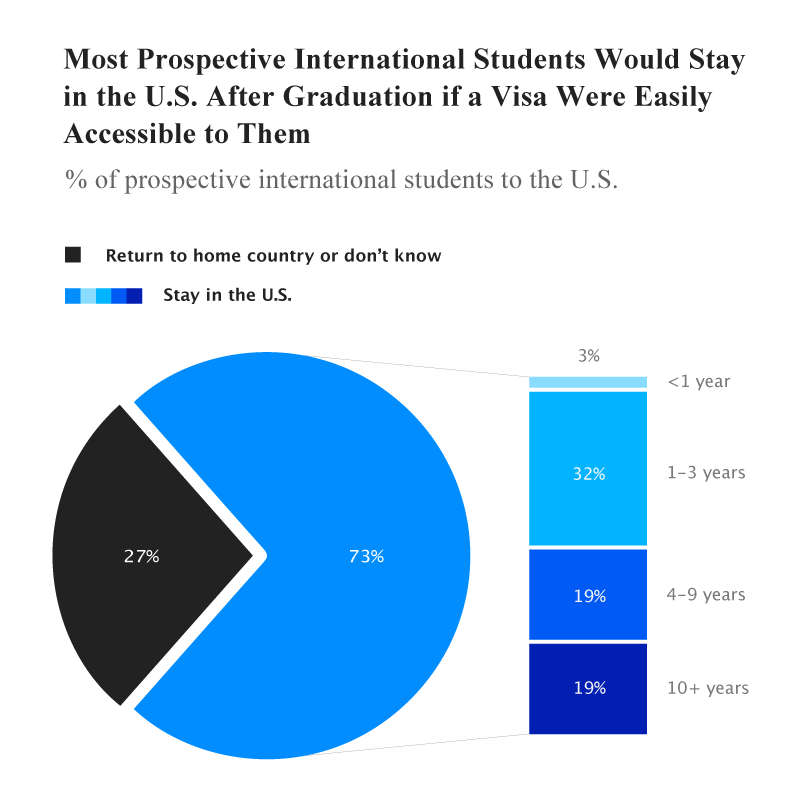

Declining international student enrollment clearly indicates the U.S. is losing its attractiveness, and our immigration policy is a critical contributing factor. A new survey commissioned by FWD.us of prospective international students suggests the problem will only get worse in the years ahead. Students choosing to study in other countries are often motivated by the ability to stay in that country after graduating, suggesting that those nations’ immigration policies are a strong attractor. For example, majorities of students who are likely to study in Canada (64%) and Australia (52%), say a straightforward process to live permanently in the country after graduation is important when selecting their country of study. By contrast, this number is a minority (47%) for students likely to study in the U.S., suggesting that the U.S. is ignoring a critical factor to attract prospective students.

While other countries promising accessible opportunities to stay and work have seen their recruitment efforts surge, the lack of a straightforward path for international student graduates to stay permanently and eventually acquire U.S. citizenship has been forcing the U.S. to lose out on recruiting top talent.1

The U.S. needs international student graduates to help fill talent shortages

America will feel the consequences of losing the global race for talent as much at home as on the global stage. Talent shortages for STEM-related jobs, for example, persist in the U.S., even as we enter a postpandemic economy. Today, the U.S. has 3 million job vacancies in professional/business service and healthcare/social assistance industries, up from about one million vacancies in 2010.2

STEM industries facing dire shortages include occupations such as physicians, computer engineers, scientists, and mathematicians—jobs that are critical to fill for the U.S. to meet emerging healthcare needs for an aging population, grow our global competitive advantage, deliver needed advancements in science and technology, and respond to ever-changing national security needs. These industries have largely maintained a 5% or higher rate of job openings during the past decade, even during and after the pandemic.

While these industries are searching desperately for more workers, thousands of international students educated in the U.S. and trained in these important fields return to their home countries each year, a major loss to the U.S. economy. For example, some 16% of all graduates from STEM-related fields are international students, including nearly half of STEM master’s (48%) and PhD (45%) graduates. These professionals, if they could remain permanently in the U.S., could contribute greatly to the U.S. economy. Failing to create a mechanism for retaining talented international students educated in the U.S. results in a self-imposed disadvantage for the United States.3

Thousands of international student graduates want to stay and work in the U.S.

Despite these challenges, the U.S. continues to attract top talent, and the missed opportunities of the past decade can still be turned around. Using government data and a recent international survey of prospective international students, FWD.us estimates that, on average over the next decade, as many as 100,000 international student graduates each year— including 66,000 in business management, health, and STEM-related fields—would like to stay and work in the U.S. for the long term if a straightforward process for permanent residency were available to them. Such a policy, if enacted by Congress, could reduce shortages in business management, health, and STEM-related jobs by a quarter this decade.

Because our immigration system has not seen substantial updates in decades, international graduates rely upon Optional Practical Training (OPT), an extension of their student status to allow them to stay and work in the U.S. in their field of study for one year, plus an additional two years for individuals with STEM degrees. The number of international students staying and working in the U.S. extension program has increased dramatically in recent years. If international student graduates wish to continue working in the U.S. beyond their time on OPT, an employer likely attempts to obtain them a specialty occupation visa, such as an H-1B visa.

For more information on current and recommended policies for international student graduates accessing permanent residency in the U.S., see our policy blog.

However, specialty occupation visas and employment-based green cards have numerical limits that are significantly smaller than the number of graduates being sponsored by American employers. And complicated prioritization limits squeeze out many international student graduates from working permanently in the United States. These caps, among other immigration policies, have created an arduous process for international students who want to stay in the U.S., creating bottlenecks at multiple points along the path. Because of these challenges, many international students return home soon after completing their studies, rather than putting their talents to work here.

Retaining international student graduates would considerably grow the U.S. economy

FWD.us estimates that the economy could expand by up to $233 billion over the next decade through these graduates’ economic contributions if graduates could work permanently in the U.S. The U.S. could experience an even larger economic impact when some of these graduates start businesses in the U.S. About 2 in 5 Fortune 500 companies, for example, were started by immigrants or children of immigrants. And, each immigrant with an advanced degree, on average, adds even more jobs to the economy. Consequently, granting international student graduates a pathway to permanently remain in the U.S. and eventually obtain U.S. citizenship could reap even greater economic dividends than their own wages.

The Biden Administration has developed an action plan to strengthen international education, including increasing the recruitment and retention of international students, and has made some initial changes such as adding more STEM categories for graduates applying for a temporary visa. At the same time, however, the administration has been slow to act, compounded by lengthy immigration processing delays at United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

Some opportunities for international graduates can be expanded by executive action, but Congress still needs to act. Congress should immediately introduce legislation allowing international students a clear avenue to permanent residency after their graduation. This would benefit the U.S. economically as we compete with other nations for highly skilled talent, and grow our economy through increased immigration.

International students need to know that, if they successfully complete their study in the U.S., they are not only welcomed, but actively encouraged, to put their education, training, and skills to work here in the United States. It’s a smart policy for international students. It’s an even smarter policy for America.