Recommendations

One of the challenges in reforming parole is that there are as many parole systems as there are states. While practices differ widely across the country, there are practices that would help ensure a fairer process for incarcerated individuals and their families everywhere. Ensuring people have a meaningful opportunity at release promotes rehabilitation and ultimately protects public safety. Research consistently shows that offering genuine, attainable pathways to parole release benefits not only incarcerated individuals but also correctional facilities and broader public safety. When a state restricts mechanisms of release or removes incentives for early release, it experiences drastic consequences in terms of institutional behavior. Early release opportunities, such as parole, are also widely popular among voters. Recent polling conducted by FWD.us found that 72% of likely voters support expanding parole to allow more people to be considered for release by a parole board.

Studies show that policies restricting or reducing parole and earned time credit increase misconduct—violent misconduct, in particular—in prisons. For instance, after Florida enacted a "truth-in-sentencing" law that significantly reduced early release, people sentenced under the new regime had 91.1% greater odds of committing a prison infraction and 56.3% greater odds of committing a violent infraction. North Carolina saw similar results, with a 19.4% increase in disciplinary conviction rates following comparable legislation.

The evidence points in one direction: meaningful release opportunities work. The following recommendations address the systemic shortcomings identified in our case studies and offer a path toward fairer, more effective parole systems.

Recommendations for a Fairer Parole Process

The tension between discretion and guidelines presents a genuine challenge for parole reform. Too much reliance on rigid guidelines or flawed risk assessments can produce unjust results; too little structure can enable arbitrary decision-making. The answer is not to eliminate discretion but to ensure it operates within meaningful guardrails that prioritize evidence of rehabilitation and provide clear standards that individuals can work to meet.

1. Increase Procedural Fairness and Transparency

a. Create Clear Standards with Real Accountability

A fair parole system should convey, with some certainty, what is required to receive parole and grant parole once those requirements are met.

States should establish clear, measurable, and attainable criteria for parole release. When boards depart from these criteria, they should be required to provide detailed, individualized explanations – subject to meaningful review by an independent body.

b. Adopt Presumptive Parole and Grid Release Mechanisms

States can also ensure that standards are applied consistently by adopting release mechanisms like grid release and presumptive parole.3 Presumptive parole or grid release allows individuals to be released if specific evidence-based criteria are met, such as eligibility based on offense, engagement in rehabilitative programs, and demonstrated readiness for reintegration into the community.

As shown in Missouri, opportunities for automatic release upon meeting certain standards do not endanger the public. Mississippi has a similar presumptive parole system in law that has never been implemented. Other states, including Oklahoma and South Dakota, have also effectively used these systems to ensure individuals who are ready and safe to be released are not held unnecessarily past their parole eligibility dates, and parole board time is spent on more difficult cases.

c. Increase Transparency and Accountability

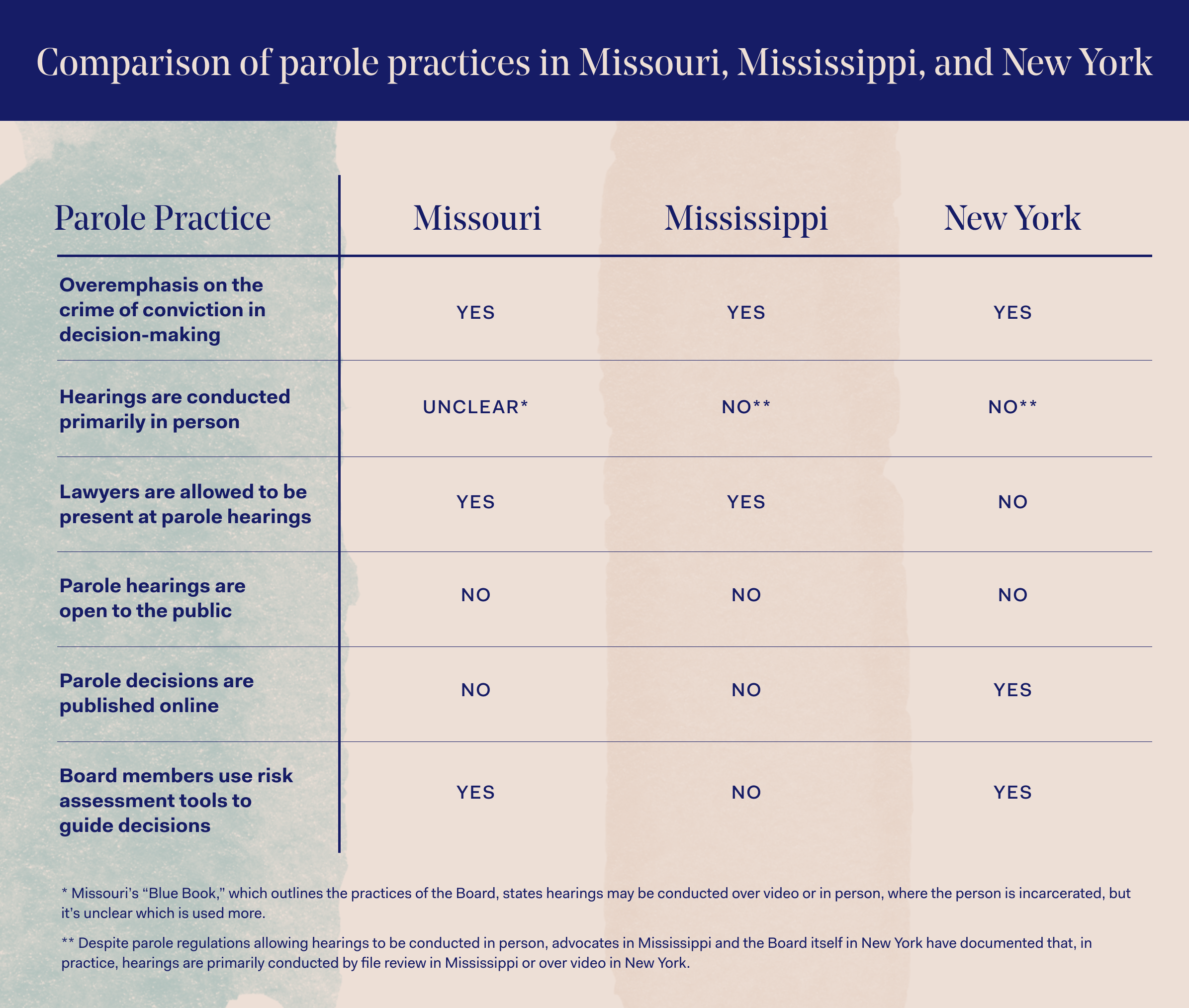

It is also important to have a transparent system in place. Parole systems with broad confidentiality provisions, such as in Missouri and Mississippi, limit external accountability. Neither state's hearings are open to the public, and neither do they publish their parole decisions or reasons for parole denials. There is no check on bias or arbitrary decision-making. Currently, only 15 states with discretionary parole publish individual parole decisions online, including New York. Four states – Massachusetts, Montana, Rhode Island, and Utah– also publish the reason for parole denial.

Parole hearings should be open to people of the incarcerated person’s choosing, including lawyers and members of the public who can demonstrate community ties and speak to release plans. States should require disclosure of all information the Board relies upon in making decisions, providing incarcerated individuals the opportunity to review and respond to adverse information during the process. This transparency serves multiple purposes: it allows individuals to understand what steps might improve their chances in future hearings, it enables external oversight of Board decision-making, and it builds public confidence that release decisions are made fairly and consistently.

2. Reform Decision-Making Criteria

a. Center Decision on Rehabilitation and Current Risk

Parole boards should be required to give primary weight to evidence of rehabilitation. One of the biggest impediments to parole release currently is parole boards’ overemphasis on static, non-changing factors, particularly the crime of conviction. That is also the one factor that incarcerated individuals cannot alter.

Parole boards should instead be required to evaluate evidence of rehabilitation – factors like program completion, educational achievement, institutional conduct, and reentry planning. These are the considerations that were not in existence at the time of the original criminal adjudication. They reflect the work that the person has put into personal transformation. Prioritizing anything else essentially elevates the opinion of the parole board over that of the sentencing judge, the legislature that established parole eligibility, and ultimately the public who elected those legislators.

3. Ensure a Meaningful Hearing Process

a. Require In-Person Hearings

States should guarantee in-person hearings for all parole-eligible individuals, outside of grid or presumptive release, with adequate time for incarcerated individuals to speak on their rehabilitation and readiness for reentry. While virtual hearings offer logistical advantages, they should be the exception, not the rule, given their documented shortcomings and lack of personal connection.

b. Allow Legal Counsel at Hearings

All states should allow incarcerated individuals to have access to a lawyer or representative of their choice during their parole hearing. This access would allow incarcerated people to respond effectively to the parole board’s concerns and make a compelling case for their release.

c. Mandate Representation of Board Members with a Background in Social Work or Behavioral Health

A national analysis of parole boards in 2023 found that nearly half of board members have a background in law enforcement, as a lawyer, or as a judge, compared to just 11% who have a background in social work. The states examined currently have no requirements reserving a certain number of parole seats for individuals with non-law enforcement backgrounds. Although New York lists qualifying professional experiences for appointment to the Board, including expertise in social work, psychology, or sociology, it does not mandate representation from these fields. States should diversify their parole boards by requiring a minimum number of members to have experience in behavioral health and social work to ensure balanced perspectives and a fuller consideration of rehabilitation and reentry.