Introduction

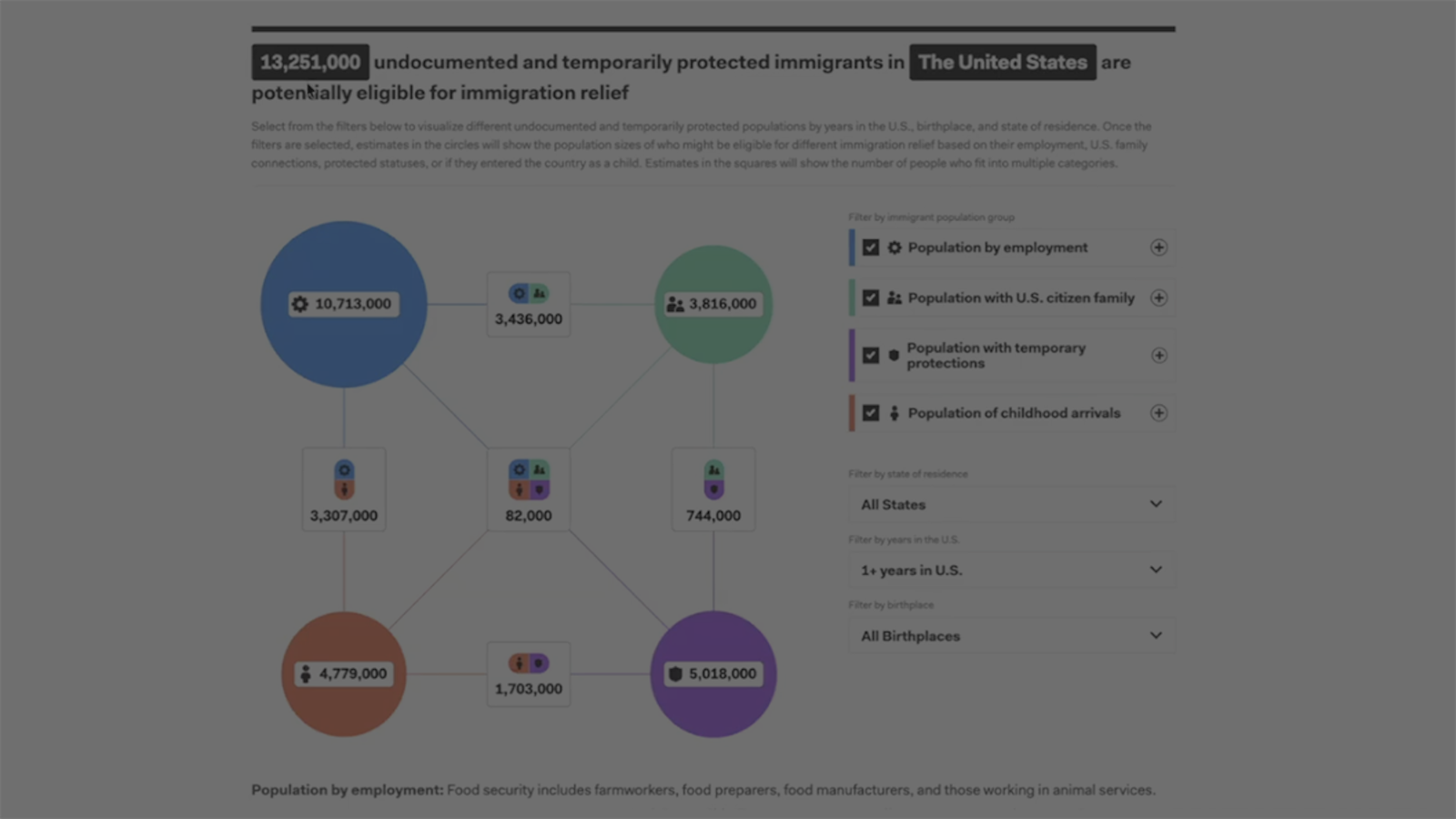

The undocumented population has changed. As of 2024, roughly 40% had some sort of temporary protection from deportation, with many having access to work permits. The population includes long-term residents and recent arrivals. And the number of childhood arrivals, many without any protections, has grown.

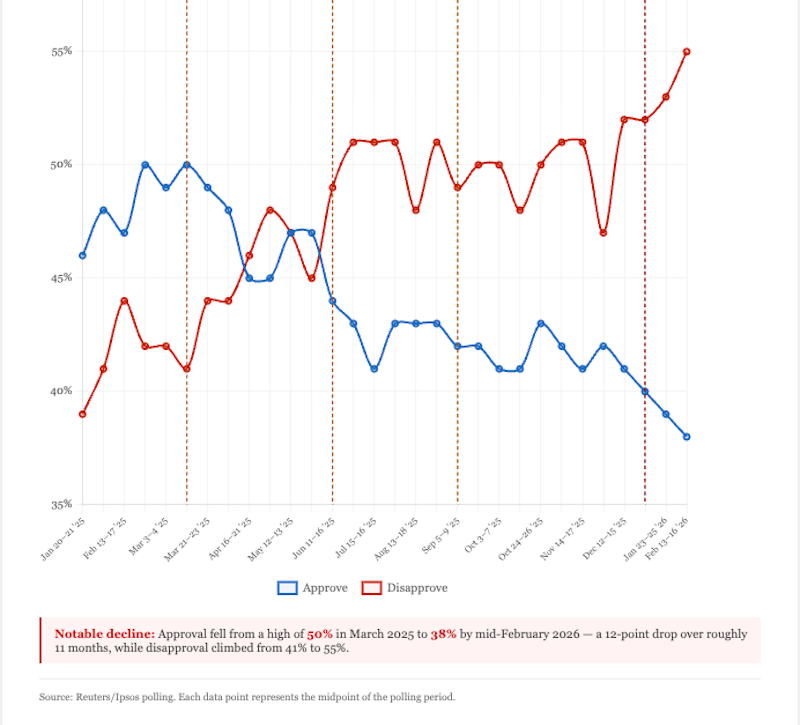

In part due to a reaction against images of families being torn apart across the country, the American public’s support for protecting undocumented immigrants has never been higher. Businesses are looking for legal pathways to retain undocumented or temporarily protected workers. In nearly every local community, individuals born in the U.S. are advocating for their undocumented neighbors.

We created this tool as a guide. This population tool maps the undocumented and temporarily protected populations, showing how different groups — employees in particular sectors, family members, individuals with a legal protection, childhood arrivals — are connected to American life. The tool also displays these populations by state of residence, country or region of origin, and time lived in the U.S. We hope this tool can support advocates and policymakers as they seek immigration relief for undocumented and temporarily protected immigrants living in their communities and across the nation.